|  |

The Republic of Colombia

is the fourth largest country in South America, with an area about two times

the size of Texas, and is bordered by Venezuela to the east, Ecuador, Peru and

Brazil to the south, the Pacific Ocean to the west, Panama to the northwest,

and the Caribbean Sea to the north. Colombia has a population of about 40 million

and an annual growth rate of approximately 1.6%. There are 32 administrative

regions (called 'departamentos') in Colombia, plus the capital district which

is its own autonomous administrative region; these administrative regions are

shown in Figure 1. Most Colombians live in the western coastal area of

the country; the region east of the Andes mountain chain is sparsely populated.

The capital city, Bogotá, is located in the center of the country and has a

population of about 6.4 million; other major cities include Cali (2.2 million),

Medellín (2 million), and Barranquilla (1.3 million). Colombia's currency,

the Colombian peso, has an exchange rate (as of February 2003) of about 2,930

pesos per U.S. dollar (i.e., one peso equals $.00034). The nominal gross domestic

product (GDP) for Colombia in 2000 was an estimated $91.5 billion and the

GDP for the year 2001 was forecasted to be $92.7 billion. Colombia is a

member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International

Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Republic of Colombia

is the fourth largest country in South America, with an area about two times

the size of Texas, and is bordered by Venezuela to the east, Ecuador, Peru and

Brazil to the south, the Pacific Ocean to the west, Panama to the northwest,

and the Caribbean Sea to the north. Colombia has a population of about 40 million

and an annual growth rate of approximately 1.6%. There are 32 administrative

regions (called 'departamentos') in Colombia, plus the capital district which

is its own autonomous administrative region; these administrative regions are

shown in Figure 1. Most Colombians live in the western coastal area of

the country; the region east of the Andes mountain chain is sparsely populated.

The capital city, Bogotá, is located in the center of the country and has a

population of about 6.4 million; other major cities include Cali (2.2 million),

Medellín (2 million), and Barranquilla (1.3 million). Colombia's currency,

the Colombian peso, has an exchange rate (as of February 2003) of about 2,930

pesos per U.S. dollar (i.e., one peso equals $.00034). The nominal gross domestic

product (GDP) for Colombia in 2000 was an estimated $91.5 billion and the

GDP for the year 2001 was forecasted to be $92.7 billion. Colombia is a

member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International

Monetary Fund (IMF).

| DC - Distrito Capital de Santa Fé de

Bogotá AMA - Amazonas ANT - Antioquia ARA - Arauca ATL - Atlántico BOL - Bolívar BOY - Boyacá CAL - Caldas CAQ - Caquetá CAS - Casanare CAU - Cauca CES - Cesar COR - Córdoba CUN - Cundinamarca CHO - Chocó GUA - Guainía GUV - Guaviare HUI - Huila LAG - La Guajira MAG - Magdalena MET - Meta NAR - Nariño NSA - Norte de Santander PUT - Putumayo QUI - Quindío RIS - Risaralda SAP - San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina SAN - Santander SUC - Sucre TOL - Tolima VAL - Valle de Cauca VAU - Vaupés VID - Vichada |

The Colombian government continues to be troubled by four decades of fighting a rebel insurgency which has consisted of the leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the National Liberation Army, and the right-wing paramilitary United Self Defense Forces of Colombia. Insurgent attacks on oil and gas pipelines, transmission lines, and other crucial infrastructure have long plagued the country, but even though the rebels have a considerable following in rural areas, they lack the military and popular support to force any change in the government. The Oleoducto Caño Limón-Coveñas oil pipeline, in particular, has been extremely vulnerable to attacks by Colombia's insurgent forces because it runs mostly above ground in sparsely populated areas that have a high rebel presence. Electricity transmission towers have also proven to be easy targets; a bombing campaign has destroyed about 400 of them, causing repeated power outages in many parts of the country. Rail lines used to transport coal have been attacked as well.

Transition from a highly regulated economic regime to an unrestricted access market has been underway in Colombia since 1990. At that time, the Colombian government introduced several policies to spur economic development and promote private enterprise. In 1994, the government enacted Laws 142 and 143 that provide the current framework for the electricity sector. Law 142 established that the provision of electricity, telecommunications, water, sewage, and bottled gas distribution are essential public services that may be provided by both public and private entities. Law 143 encouraged greater private sector involvement in the power sector, and separated the electricity industry into separate generation, transmission, and distribution components.

The key governmental body involved in the energy sector in Colombia is the Ministry of Mines and Energy, which is responsible for the overall policy making and supervision of the electricity sector in Colombia. It regulates generation, transmission, trading, interconnection, and distribution, and approves generation and transmission programs. The ministry delegates supervisory authority over the electricity sector to a number of its agencies, specifically Comisión Reguladora de Energía y Gas (CREG) and Unidad de Planeacion Minero Energetica (the Union of Mineral and Energy Planning, or UPME). CREG regulates the transportation and distribution of electric power and gas and adjusts policies and procedures by which these services can reach the consumers and allow market competition between providers.

In Colombia, the state owns all hydrocarbon reserves. Control is exercised in the oil and gas sectors through state-run hydrocarbons companies Empresa Colombiana de Petróleos (Ecopetrol) and Empresa Colombiana de Gas (Ecogás). While Colombia is South America's largest coal producer, almost 70% of the country's electric power comes from hydroelectric sources. The government is seeking to encourage greater use of natural gas for electricity generation and public transportation in its Plan de Masificacion de Gas Natural (Natural Gas Mass Consumption Plan).

In July 2002 the government signed a law revising its hydrocarbons royalties scheme in a bid to attract more foreign investment in oil and gas exploration. The law cuts royalties on recent discoveries of oil fields producing less than 125,000 barrels per day (b/d) to between 8% and 20% (depending on daily output) from the long-standing, flat rate of 20%. To put this into context, only the country's largest fields, the Cusiana-Cupiagua fields, exceeds 125,000 b/d. The purpose of the revision is to better compensate foreign oil companies for the country's instability and risk of violence. The sliding royalties formula is opposed by provinces with substantial oil reserves that depend heavily on revenue streams from oil fields. Provinces keep 60% of the royalties with the rest going to Bogota.

CREG has released a series of incentives for promoting development of natural gas in the Cusiana-Cupiagua fields. Among other things, the new plan eliminates the $0.10-per-million Btu pipeline transport charge previously levied; instead, gas producers will now pay a separate transportation fee for shipping natural gas through Colombia's gas pipelines. CREG also will now allow partners to enter export agreements for projects where the reserves will last six years or more. Another improvement outlined in the CREG plan will allow gas producers to jointly sell their gas, whereas each company now has to sell its gas individually.

Colombia possesses numerous fossil fuel and natural resources. The country has productive petroleum reserves, extensive coal reserves (the largest in South America), significant but largely untapped natural gas reserves, and extensive hydroelectric resources. A large amount of potentially productive oil and natural gas areas remain unexplored. Demand for energy (petroleum, natural gas, and electricity) is expected to grow 3.5% per year through 2020.

An historical summary of Colombia's total primary energy production (TPEP) and consumption (TPEC) is shown in Table 1.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| TPEP | 1.93 | 1.87 | 1.90 | 1.99 | 2.01 | 2.41 | 2.61 | 2.85 | 3.07 | 3.21 | 3.09 |

| TPEC | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.18 | 1.18 |

Oil

Exploration and

Reserves

Ecopetrol, while attached to the Ministry of Mines and

Energy, possesses legal existence, administrative and decision-making autonomy,

and its own, independent capital. Ecopetrol is responsible for exploring,

extracting, processing, transporting, and marketing Colombia's hydrocarbon

resources. Colombia's petroleum reserves currently stand at 1.75 billion

barrels (as of January 2002), down from 1.97 billion in 2001. Colombia has

vast untapped oil potential reserves and its crude oil tends to be of a better

quality than the oil from most of its Latin American neighbors, with its three

export crudes ranging from 20° to 36° API. The Cusiana-Cupiagua fields are

presently the most well developed of Colombia's oil resources, with a combined

reserve of 1.6 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The crude oil from that

field is a light sweet crude with a 36.3° API gravity and 0.26% sulfur

content.

There are 18 sedimentary basins in Colombia, covering a total of 1,036,400 square kilometers with about 200,200 square kilometers under actual exploration and production activity. Only seven of these basins have so far seen commercial oil production -- the Upper, Middle, and Lower Magdalena Valleys, Llanos Orientales, Putumayo, Catatumbo, and Guajira basins. The hydrocarbon resource potential of the seven basins is estimated to be 26 billion barrels of oil equivalent, while the potential of the remaining eleven basins is estimated to be 11 billion barrels of oil equivalent.

The discovery of the Guando oil field in June 2000 has given government officials reason for optimism of reaching their goal of continuing to be an exporter of petroleum. Guando, located in the Upper Magdalena Basin 90 kilometers southwest of Bogota, is the third largest oilfield of the last 20 years in Colombia, and the largest since BP's discoveries at the Cusiana-Cupiagua fields in 1989. Proven reserves are 118 million barrels. The discovery was made by a joint venture between Canada's Nexen and Brazil's Petrobras, and Petrobras has since successfully drilled 10 wells which are producing nearly 2,000 b/d. The joint venture hopes output of 28° API crude will hit 10,000 b/d by 2003, and 30,000 b/d by 2005. The two companies are working on a deal with Ecopetrol whereby Guando's output would be split evenly between the joint venture and Ecopetrol.

In February 2002, meaningful discoveries were made in the Capachos and La Hocha fields that could add 250 million barrels of crude to Colombia's reserves. Capachos is situated 124 miles east of Bogota in the Piedemonte region, in the eastern province of Arauca, and is operated by Repsol-YPF, TotalFinaElf, and Ecopetrol. The field is currently producing about 2,000 b/d of 37° API crude and 1.5 million cubic feet per day of natural gas. La Hocha is located 186 miles south of Bogota in the Upper Magdalena Valley region in the southern province of Huila and is operated by Hocol, a Saudi-Colombian joint venture. Production there is presently only about 500 b/d, however. Both fields are expected to be in full production by 2005. Other recent discoveries include fields in the Casanare-Arauca area and near the upper River Magdalena, both with estimated reserves of 100 million barrels each. Full production at those fields is scheduled for 2005.

Another promising basin is Putumayo, in southern Colombia, which Ecopetrol estimates could hold 2.4 billion barrels of oil. Exploration of the area faces daunting challenges as it is in the center of the country's cocoa cultivating region, an area contested by rebels on the right and left. In August 2002, Ecopetrol signed a contract with Petrominerales, the Colombian subsidiary of Canada's Petrobank for the Moqueta A and B blocks in Putumayo. The two blocks cover 30,000 hectares of rain forest near the Ecuadorian border, which will bring environmental aspects into consideration if and when production activities commence.

Ecopetrol believes the Llanos and Magdalena basins have good prospects for oil exploration. The company is hoping development of 16 potential sites in the two basins will raise crude oil reserves by 2.8 billion barrels. The sites could hold between 200 million and 900 million barrels of crude each.

The Niscota field in Piedemonte could hold reserves as high as 900 million barrels, and Ecopetrol believes the field could be producing 250,000 b/d by 2010. Exploration is underway in the Upper Magdalena Valley. Several companies, including Brazil's Petrobras and Hocol are drilling high-risk wells in the region.

The Uribe Administration is eyeing areas outside of rebel strongholds for future oil exploration, such as offshore tracts. Areas around the islands of San Andrés and Providencia in the Caribbean are believed to hold 7 billion barrels of reserves. The islands could be very attractive to foreign oil companies because of their relative safety, and the Colombian government is offering more generous royalty terms to counter the perceived higher risk of doing business in Colombia because to the ongoing insurgency. The two islands, however, are the subject of a territorial dispute; they have been a part of Colombia for nearly 100 years, but are also claimed by Nicaragua.

Changes to laws related to hydrocarbons exploration since 2000 have helped Colombia secure more exploration contracts with foreign companies. Ecopetrol has signed 77 exploration contracts between 1999 and August 2002. Some 30 contracts were signed in 2001 and seven have been signed in 2002 (through August). One main change was the reduction of Ecopetrol's share of the field (from 50% to 30%) once commerciality was declared.

In August 2002, Argosy Energy International became the first company to sign a contract under the so-called "Adjacent Prospects Contract Model" recently adopted by Ecopetrol to provide greater incentives for oil exploration, and has been awarded rights to a 20,000-hectare area called the Guayuyaco prospect, in Putumayo. The adjacent prospects contract structure grants Argosy a 70% share of any discoveries (up from 35%), and cuts royalties from the current 20% to a sliding scale that starts with 8% for the first 5,000 b/d. Argosy places recoverable reserves for its block at 170-230 million barrels, of which 60-90 million barrels are held in five areas that have already been identified using 2D and 3D seismic data, electric well logs, and production figures from nearby fields. The company has committed to drilling one well by October 2003 and has obtained the necessary environmental permits. It is hoped the well will become operational immediately, producing 2,000-3,000 b/d. Argosy is also active in oil exploration in Colombia through its Santana and Río Magdalena contracts.

In general, independent oil companies are now very active in Colombia. Companies are allowed to enter into joint ventures with Ecopetrol with the requirement being that Ecopetrol must hold at least a 30% stake. Foreign players include Chevron-Texaco, Braspetro International, TotalFinaElf, Cepsa, Repsol, Talisman, Sipetrol, Nexen, Hocol, Lukoil, among others with Britain's BP and U.S. Occidental having the largest presence.

Production and Consumption

Colombia is

Latin America's third leading oil producer. After several years of declining

production (due in large part to progressive depletion of older fields and rebel

attacks on pipelines), oil output is beginning to rise as recent finds begin to

come into production. Ecopetrol has upgraded its 2002 production estimates from

535,000 b/d to 575,000 b/d and indicated production may hit

600,000 b/d in 2003.

BP Amoco, which has invested about $3 billion in Colombia to date, operates the Cusiana-Cupiagua fields (source of nearly half of Colombia's production) on behalf of a group of companies that includes Ecopetrol (50% interest), BP Amoco (19%), Total (19%), and Triton (12%). Output from the Cusiana/Cupiagua fields has been dropping from a peak of 440,000 b/d in 1999 to an estimated 240,000 b/d in 2002, and analysts expect output to further decline to 220,000 b/d in 2003. The Cano-Limon field, located in Colombia's eastern plains, is the second leading field but is also in decline; production was 76,533 b/d in June 2002, down from from about 125,000 b/d in 1999. The crude oil from this field is also of high quality, with an API gravity of 29.5°. Occidental Petroleum operates and has a 35% working interest in the Cano-Limon field.

Colombia wants to significantly boost oil production by the end of the decade; Ecopetrol has raised its production target for 2010 to 850,000 b/d in a bid to maintain the country's self-sufficiency in petroleum. Without increased production levels, Colombia could become an oil importer by 2004. To reach the 2010 goal, Ecopetrol will have to drill 100 exploratory wells between 2002 and 2005 and spend $3 billion on exploration and $6.3 billion on development by 2010.

Petroleum demand in Colombia is forecast to climb 3.8% per annum through 2020, with consumption going from 11.6 million metric tons of oil equivalent (mtoe) in 2000 to 25.6 million mtoe in 2020. An historical summary of petroleum production and consumption in Colombia is shown in Table 2.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Production (total)* | 450 | 427 | 441 | 463 | 457 | 595 | 633 | 663 | 743 | 826 | 705 |

| Production (Crude Oil only) |

440 | 419 | 433 | 456 | 450 | 585 | 623 | 652 | 733 | 816 | 691 |

| Consumption | 197 | 205 | 230 | 240 | 244 | 251 | 278 | 287 | 289 | 277 | 272 |

Oil is Colombia's leading export, currently generating about $2 billion per year in revenue. The oil sector represents more than 20% of Colombia's exports as well as about 4.5% of the gross domestic product (GDP). In 2001, Colombia exported 280,000 b/d to the United States (down from 332,000 b/d in 2000, and more than 450,000 b/d in 1999). However, Colombia is incurring estimated losses of more than $900,000 per day in royalties, taxes, and state participation due to the pipeline bombing campaign. Natural decline due to maturity of oil fields also has serious implications for Colombian oil production.

Refineries and Downstream Processing

There

are five petroleum refineries in Colombia, but two of them (Barrancabermeja and

Cartagena) account for about 98% of all refining capacity. Ecopetrol is

responsible for managing all aspects related to the petrochemicals industry, as

well as management of the two Barrancabermeja and Cartagena refineries. A

summary of Colombia's oil refineries is shown in Table 3.

| Refinery | Location (Departamento) |

Capacity (b/d) |

| Barrancabermeja | Santander | 205,000 |

| Cartagena | Bolivar | 75,000 |

| Empresa Colombiana de Petroleos (Apiay) |

Meta | 2,250 |

| Tibu | Norte de Santander | 1,800 |

| Orito | Putumayo | 1,800 |

| Total | 285,850 | |

Ecopetrol wants to raise capacity at the Cartagena refinery from 75,000 b/d to 140,000 b/d. The company is soliciting bids for the $630 million project and a $25 million contract to oversee the modernization. Original plans called for the refinery to be completed in the second half of 2005, but a slight delay in assigning the management contract may delay project completion. Output from Cartagena will go to meet domestic needs. Any excess production will be shipped to the Unites States and the Caribbean.

Completion of a new cracking unit at the Barrancabermeja refinery 350 kilometers north of Bogota will increase output of fuels by 30,000 b/d and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) by 10,000 b/d. The increased capacity will enable Colombia to meet domestic demand for transportation fuels (86,000 b/d) and LPG (24,000 b/d) with output from the Barrancabermeja and Cartagena refineries. An historical summary of Colombia's refined petroleum products output is shown in Table 4.

| Refined Product | Production Rate | |||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | |

| Motor Gasoline | 88 | 85 | 87 | 84 | 86 | 81 | 113 | 104 | 107 | 116 |

| Jet Fuel | 10 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 18 |

| Kerosene | 8 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Distillate Fuel Oil | 43 | 46 | 64 | 64 | 58 | 56 | 66 | 68 | 64 | 58 |

| Residual Fuel Oil | 66 | 78 | 70 | 67 | 58 | 62 | 56 | 58 | 55 | 61 |

| Liquefied Petroleum Gases | 15 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 17 | 27 | 16 | 22 | 18 | 22 |

| Lubricants | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other * | 7 | 15 | 12 | 21 | 16 | 28 | 17 | 45 | 60 | 53 |

| Total | 237 | 257 | 266 | 268 | 263 | 272 | 292 | 317 | 318 | 333 |

| Refinery Fuel and Loss | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

Ecopetrol announced in February 2002 that a consortium is planning a new refinery at Cimitarra, in the Province of Santander, to refine Cusiana-Cupiagua crude and which would become operational in 2004. Capital for the proposed refinery will come from the World Bank, the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and a U.S.-Mexican consortium.

Natural Gas

Exploration and

Reserves

Colombia has proven reserves of natural gas (estimated in

January 2002) at 4.3 trillion cubic feet (tcf), which represents a

significant decrease from the preceding year's estimate of about 6.9 tcf.

Colombia's potential gas reserves are estimated to be about an order of

magnitude greater, however. Colombia's natural gas resources are located mainly

in the Northern Coast and Barranca regions and in La Guajira departamento in

northern Colombia. The La Guajira basin in northern Colombia along the Caribbean

coast is believed to have the best potential for large, untapped reserves.

Recent increases in natural gas prices have attracted investors to Colombia's Caribbean coast in search of natural gas. In particular, the offshore Chuchupa and Ballena oil and gas fields, both operated by ChevronTexaco, are believed to hold reserves of 6.4 tcf and 870 billion cubic feet (bcf), respectively; a thorough exploration of these fields for gas resources began in 2001. In 2000, Canadian hydrocarbons companies Millennium Energy, Inc. and Mera Petroleum Inc. signed an agreement with Ecopetrol to explore for natural gas in the onshore Salinas block in La Guajira departamento. The concession area for these two companies may contain as much as 2 tcf of natural gas. As of December 2002, Mera and Millennium were awaiting a decision by Ecopetrol to extend their drilling rights in the Salinas block until October 2003. The seismic work has been completed; cost of the initial drilling phase is expected to be around $2 million.

Downstream Processing

Plans are underway

to construct a facility at the Cusiana-Cupiagua oil fields for processing

associated natural gas and have it operational by 2004-5. BP Amoco and Ecopetrol

are considering investing $120-130 million in the plant.

Production and Consumption

Most of

Colombia's natural gas production occurs offshore in the Guajira region. The

Chuchupa and Ballena gas fields produce about 80% of the output, averaging

500 million cubic feet per day.

Historically, natural gas production and consumption in Columbia have been in lock-step for many years. This may change if, as is expected, a gas export industry eventually comes into existence in response to the new CREG incentive plan. This will not happen in the very near future, however, as the amount of proven gas reserves is thought to be still too small to support large-scale export activities. For the near term, greatly increased domestic usage of natural gas is much more likely to occur.

The Colombian government is forecasting 3.1% annual growth in natural gas consumption through the end of the next decade. Demand is predicted to climb from 1.4 million mtoe to 2.6 million mtoe in 2020, due chiefly to the construction of new gas-fired power plants. The government has also been promoting the use of natural gas to its citizens as a low-cost alternative energy source (the cost of natural gas as an energy source is only one-fifth of that of electricity in Colombia).

An historical summary of natural gas production and consumption in Colombia is shown in Table 5.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Production | 0.151 | 0.155 | 0.151 | 0.157 | 0.162 | 0.161 | 0.167 | 0.211 | 0.221 | 0.183 | 0.201 |

| Consumption | 0.151 | 0.155 | 0.151 | 0.157 | 0.162 | 0.161 | 0.167 | 0.211 | 0.221 | 0.183 | 0.201 |

Coal

Reserves and

Mining

Colombia has proven recoverable coal reserves of

7.44 billion short tons, more than 94% of which is anthracite and

bituminous coal. The majority of coal reserves are found in northern Colombia,

in Cesar departamento and also on the Guajira (Cerrejon) peninsula, which is

home to the Cerrejon Zona Norte mine, the largest open pit coal mine in the

world and the largest coal mining operation in Latin America. The Cerrejon Zona

Norte mine by itself possesses more than a billion tons in reserves of a very

desirable tertiary, low-ash, low-sulfur, non-caking bituminous coal. Production

from the mine was 20.2 million short tons in 2000 and about 22 million

tons in 2001. Over 80% of the mine's production is exported to Europe.

In 2001 the Colombian government sold off the state-run coal company Carbones de Colombia (Carbocol). This sale was one of the IMF requirements for obtaining a $2.7 billion loan package; the purchaser was a group headed up by U.K.'s Billiton and Anglo American, and Switzerland's Glencore. The sale netted $384 million for the government, but critics have claimed that the price was too low. Carbocol now has a 50% equity interest in the Cerrejon Zona Norte coal mine, with the other half owned by Intercor, an ExxonMobil subsidiary. Carbocol and Intercor hold the right to operate Cerrejon Zona Norte until 2033.

One of the other major coal mines in Colombia is the Pribbenow Mine, located near La Loma in Cesar departamento, which has estimated reserves in excess of 534 million tons of high Btu, low-ash, low sulfur coal. The mine is operated by the U.S.-based company Drummond Ltd., whose contract with the government-owned Colombian Mining Company (Minercol) runs through 2019. Drummond is expected to increase its cumulative capital investment in the coal industry in Colombia to $1 billion. This additional expenditure would increase its output from 6 million tons to 12 million tons annually.

The Colombian government has awarded a $12.5 million 25-year contract to operate the Patilla coal mine on the Guajira peninsula to Carbocol. The mine has 65 million metric tons of proven reserves of high quality coal, and yearly output is 3-4 million metric tons.

Production, Consumption, and Exports

Coal

plays a significant but not major role in Colombia's energy picture from the

standpoint of electricity generation. Most of the coal mined in Colombia (almost

90%) is exported; coal is Colombia's third leading export and Colombia is Latin

America's leading coal exporter. In 2000, Colombia was the largest exporter of

coal to the United States with exports of primarily steam coal totaling

7.6 million tons. The coal industry in Colombia is aggressively seeking to

expand its current exports by 2010 to greater than 70 million tons.

An historical summary of coal production and consumption in Colombia is shown in Table 6.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Production Anthracite Bituminous Lignite |

22.56 n/a 22.56 n/a |

22.04 n/a 22.04 n/a |

24.15 n/a 24.15 n/a |

23.39 n/a 23.39 n/a |

24.98 n/a 24.98 n/a |

28.37 n/a 28.37 n/a |

33.14 n/a 33.14 n/a |

35.93 n/a 35.93 n/a |

37.20 n/a 37.20 n/a |

36.11 n/a 36.11 n/a |

42.04 n/a 42.04 n/a |

| Consumption | 3.04 | 5.51 | 6.18 | 6.35 | 6.07 | 5.05 | 5.27 | 5.56 | 5.67 | 4.38 | 4.71 |

Colombia has abundant water resources for hydroelectric power, and is second only to Brazil in hydroelectric potential in Latin America. Hydroelectric sources presently provide more than 70% of Colombia's electricity power generation. Much of Colombia's hydroelectric generation is located in the mountainous northwest part of the country, which produces about 40% of the hydroelectric power, or a bit more than one-quarter of the total electricity generation. Several of the power plants in Antioquia departamento are actually sited between two rivers, being supplied with water from one and emptying the water into another after it passes through the turbines. A map with the location of some of these power plants is shown in Figure 3.

There are presently three hydroelectric facilities in Colombia of greater than 1,000 megawatts (MWe) in capacity and another dozen of greater than 200 MWe. Colombia's hydroelectric generating capacity is split among many companies. Empresas Publicas de Medellín (EPM), headquartered in Antioquia departamento, presently operates eleven hydroelectric facilities of at least 10 MWe, representing more than 2,100 MWe total hydroelectric generating capacity. Other companies with significant hydroelectric generation capacities include ISAGEN (headquartered in Bogotá), with more than 1,800 MWe (most of which is the San Carlos Power Plant, presently Colombia's largest-capacity hydroelectric facility), Empresas Energia del Pacifico (EPSA), Empresa de Generación (EMGESA), and AES Bolivar. Besides these, there are several smaller companies who own relatively minor amounts of hydroelectric generating capacity.

The most recent hydroelectric facility to come online was the $600 million 396 MWe Miel I power plant, which began operations in August 2002 and came fully online in October 2002. The facility is owned and operated by Hidromiel which is itself owned by a consortium of companies including ISAGEN. ISAGEN has a 30-year power purchase agreement for the plant's electricity generation.

A summary of Colombia's largest hydroelectric power plants is shown in Table 7.

| Generating Facility | Owner | Location | Capacity (MWe) | |

| River | Departamento | |||

| San Carlos | ISAGEN | San Carlos; Samana Norte |

Antioquia | 1,240 |

| Guavio | EMGESA | Guavio | Cundinamarca | 1,189 |

| Chivor | AES Bolivar | Bata | Boyacá | 1,000 |

| Guatapé | EPM | Magdalena; Guatapé |

Antioquia | 560 |

| Betania | Central Hidroeléctrica de Betania |

Magdalena; Yaguará |

Huila | 540 |

| Guadalupe | EPM | Porce | Antioquia | 495 |

| Miel I | ISAGEN (Hidromiel) | La Miel | Caldas | 396 |

| Porce II | EPM | Porce | Antioquia | 392 |

| Alto Anchicayá | EPSA | Anchicayá | Valle de Cauca | 365 |

| Urrá (Alto Sinú) | Corp. Electrica Costa Atlantica |

Sinú | Córdoba | 344 |

| La Guaca | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 311 |

| La Tasajera | EPM | Grande | Antioquia | 311 |

| Salvajina | EPSA | Cauca | Cauca | 285 |

| Paraiso | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 270 |

| Colegio | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 250 |

| Las Playas | EPM | Guatapé | Antioquia | 200 |

| Jaguas | ISAGEN | Nare; Guatapé |

Antioquia | 170 |

| San Francisco Caldas | Central Hidroeléctrica de Caldas |

San Francisco | Caldas | 135 |

| Calima | EPSA | Calima | Valle de Cauca | 132 |

| Salto | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 127 |

| Río Grande | EPM | Grande | Antioquia | 75 |

| Bajo Anchicayá | Central Hidroeléctrica del Rio Anchicayá |

Anchicayá | Valle de Cauca | 74 |

| Laguneta | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 72 |

| Río Prado | Eléctrificadora del Tolima | Prado | Tolima | 50 |

| Canoas | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 45 |

| Troneras | EPM | Nechí | Antioquia | 42 |

| Mocorongo | EPM | n/a | Antioquia | 32 |

| Esmeralda Caldas | Central Hidroeléctrica de Caldas |

San Eugenio | Caldas | 30 |

| Calderas | ISAGEN | Calderas; San Carlos |

Antioquia | 26 |

| Florida | Centrales Eléctricas del Cauca |

Cauca | Cauca | 26 |

| Muña | EMGESA | Bogotá | Cundinamarca | 24 |

| Río Mayo | Centrales Electricas de Nariño |

Mayo | Nariño | 21 |

| Niquía | EPM | Grande | Antioquia | 20 |

| Río Piedras | Generar | Piedras | Antioquia | 19 |

| Ínsula | Central Hidroeléctrica de Caldas |

Chinchiná; Campoalegre; Cameguadua |

Caldas | 18 |

| Palmas | Eléctrificadora de Santander | Lebrija | Santander | 18 |

| La Ayura | EPM | n/a | Antioquia | 16 |

| Piedras Blancas | EPM | Piedras Blancas | Antioquia | 10 |

| Generating Facility | Owner | River | Departamento | Capacity (MWe) |

| Location | ||||

Colombia plans to further increase its hydroelectric generating capacity, and has some large projects under consideration, the biggest being an 1,800 MWe facility in Antioquia departamento. Other new hydroelectric facilities being planned includes EPM's 645 MWe Nechí project in Antioquia departamento, which could cost more than $600 million and require eight years to build. Nechí and the 136 MWe Guaico plant, another EPM facility in the planning stages, are now on hold for budgetary reasons. A summary of Colombia's planned hydroelectric facilities is shown in Table 8.

| Generating Facility | Owner | Location | Capacity (MWe) |

Status | |

| River | Departamento | ||||

| Pescadero-Ituanga | ISAGEN | n/a | Antioquia | 1,800 | Planned |

| Sogamoso | Hidrosogomoso | Sogamoso | Santander | 1,035 | Planned |

| Andaquí | ISAGEN | Caquetá | Cauca; Putumayo |

705 | Planned |

| Porce III | EPM | Porce | Antioquia | 660 | Planned |

| Nechí | EPM | Nechí | Antioquia | 645 | Planned |

| Cabrera | ISAGEN | n/a | Santander | 600 | Planned |

| Fonce | ISAGEN | Fonce | Santander | 520 | Planned |

| Calima | EPSA | Cristalina; Azul; Chanco; Calima |

Valle de Cauca | 240 | Planned |

| Guaico | EPM | n/a | Antioquia | 136 | Planned |

| Encimidas | ISAGEN | n/a | Antioquia | 94 | Planned |

| Cucuana | Eléctrificadora del Tolima |

n/a | Tolima | 88 | Planned |

| Río Amoyá | Generadora Unión | Amoyá | Tolima | 78 | Planned |

| Cañaveral | ISAGEN | n/a | Antioquia | 68 | Planned |

| Río Ambeima | Generadora Unión | Ambeima | Tolima | 45 | Planned |

| Senegal | Empresas Públicas de Pereira |

n/a | Risaralda | 30 | Planned |

| Cocorná | Empresa Antioqueña de Energia |

n/a | Antioquia | 29 | Planned |

| Aures | Empresa Antioqueña de Energia |

n/a | Antioquia | 25 | Planned |

| Montañitas | Generadora Unión | n/a | Antioquia | 25 | Planned |

| La Herradura | EPM | n/a | Antioquia | 24 | Planned |

| La Vuelta | EPM | n/a | Antioquia | 24 | Planned |

| Alejandría | Empresa Antioqueña de Energia |

n/a | Antioquia | 16 | Planned |

| Caracolí | Empresa Antioqueña de Energia |

n/a | Antioquia | 15 | Planned |

| Generating Facility | Owner | River | Departamento | Capacity (MWe) |

Status |

| Location | |||||

Other Renewable Energy

Colombia is moving

ahead with its first windpower project, a a 20 MWe pilot wind farm with 15

turbines in the northeastern Alta Guajira region. In February 2002, the

Colombian government provided EPM with a $6.8 million tax break for the

project; EPM will soon begin technical and feasibility studies. EPM does not

feel wind power is economically feasible under current market conditions, but

the purpose of the pilot project is to study market potential and stimulate the

market for large-scale wind plants. EPM feels the wind conditions in the Alta

Guajira region could make wind power competitive in Colombia in the near

future.

Colombia also has a reasonable amount of geothermal energy potential, though there has been no real effort to exploit it. Current utilization is limited to a few dozen geothermally-heated bathing pools which cumulatively have a thermal capacity of about 13 megawatts-thermal (MWt) and an annual energy use of about 270 terajoules. There is a 150 MWe geothermal energy project in the planning stages, sponsored by Geotermia Andina, which would be located near Villamaria in Caldas departamento.

Energy Infrastructure

Electricity Transmission

The Colombian National

Transmission System (STN) provides a viable means of transaction between

electricity generators and traders. The transmission service is a natural

monopoly that is regulated by the CREG. There are 11 companies in charge of

electricity transmission in Colombia, the largest being the

government-controlled Interconexión Eléctrica S.A. E.S.P. (ISA) which controls

83% of the electricity transmission market.

The Colombian government has been reducing its stake in ISA, selling off some equity through a public stock offering in late 2000 for $45 million. In May 2002, plans were announced for a second public offering, which is expected to net the government $55 million and reduce the government's stake in ISA to about 55%. Besides the Colombian government, the largest shareholders in ISA are EPM with about 12% of the stock, EPSA with 5%, and Empresa de Energia de Bogota (EEB) with 2.5%.

ISA is the only energy transporter in Colombia with national coverage, and has one of the largest transmission networks in Latin America. ISA owns and operates 100% of the 500 kilovolt (kV) lines and substations in the STN, and 67.4% of the 230 kV transmission lines and 43.6% of the substations in the system. ISA's transmission network includes 4,500 miles of 230 kV and 500 kV lines and a 480-mile system on the Caribbean coast it acquired when it bought the state-owned utility Codelco in 1998. ISA also operates the National Dispatch Center (CND) and the Wholesale Energy Market (MEM).

One of the main transmission lines is the 500 kV San Carlos-Cerromastoso line, which connects the Atlantic coast to the national grid. Other important transmission lines include the Playas-Oriente and Guatapé-Envigado transmission lines, which connect those two power plants to the national grid. The transmission system has one interconnection with Ecuador and two with Venezuela. In 2001, Colombia signed an agreement with Ecuador to build another line connecting the two countries electricity networks; this 230 kV line will run from Pasto, Colombia, to Quito, Ecuador, and is expected to be operational sometime in 2003.

ISA has been very aggressive in expanding its transmission network and has invested more than $600 million to expand its transmission network since 1997. These investments included 560 kilometers of 230 kV lines that were incorporated into the network, 378 kilometers of 500 kV lines, and six 230 kV substations. However, attacks by insurgents on Colombia's transmission lines in recent years have exacted a terrible toll. In one six-month period, between late 1999 to early 2000, more than 350 transmission towers were destroyed.

Oil

Pipelines

Ecopetrol, in addition to its responsibility for

exploring, extracting, processing, and marketing of oil, is also responsible for

its transportation through Colombia's oil pipelines. Colombia possesses an

extensive network of oil pipelines linking production areas to the main

refineries and to shipping ports; all of it is owned by Ecopetrol. In all, there

6,881 kilometers of oil pipelines, consisting of 2,527 kilometers of

multi-pipeline to transport fuels, 1,751 kilometers of oil pipelines for crude

transport, and 663 kilometers of fuel oil pipelines for fuel oil.

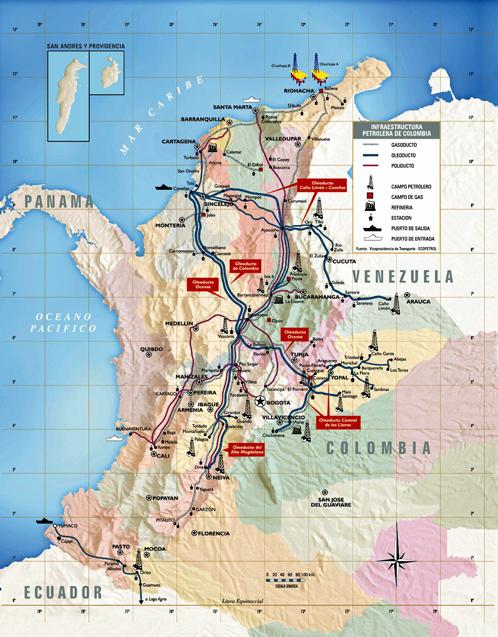

The Caribbean port city of Coveñas, in Córdoba departamento, is the terminus point for many of Colombia's oil pipelines. The 774-kilometer Oleoducto Caño Limón-Coveñas transports crude from the oilfields in the eastern Arauca province via Zulia estado in Venezuela to Coveñas for export, while the 757-kilometer Oleoducto Ocensa, with a capacity of 615,000 b/d, transports oil to Coveñas from the Cusiana and Cupiagua fields in Casanare and Boyacá departamentos. Other major oil pipelines that feed oil toward Coveñas include the Oleoducto del Alto Magdalena, which runs north from Huila departamento along the Magdalena river valley, the Oleoducto Central de Los Llanos, which funnels oil from the basins of Casinare and Meta departamentos into the Oleoducto Ocensa (as well as suppliying crude oil to the Apiay refinery), and the 481-kilometer Oleoducto de Colombia which parallels the Oleoducto Ocensa from the Magdalena valley to Coveñas. The only other major pipeline, the TransAndino, serves to move Ecuadorian and Colombian crude from the Orito field in the Putumayo basin to the Pacific port city of Tumaco in Nariño departamento. Ecopetrol operates the Oleoducto Caño-Limón Coveñas in partnership with U.S. firm Occidental Petroleum and runs the Oleoducto Ocensa together with BP.

A diagram of Colombia's major oil and gas pipelines is shown in Figure 4.

Gas Pipelines

The

two natural gas tranmission companies in Colombia are the state-owned Ecogás and

the privately-owned joint stock company Promigas. Even though Promigas'

transmission network is smaller in overall length that that of Ecogás, Promigas

moves about 60% of the natural gas transmitted throughout Colombia, mostly from

production sites in La Guajira departamento to the Jobo terminal in Sucre

departamento. In 2001, Promigas gas transmission totaled more than

350 million cubic feet. More than half of this volume was sold for utility

electricity generation.

The Colombian gas pipeline system consists of 378 kilometers of propane pipelines for the transportation of LPG, 1,001 kilometers of gas pipelines for natural gas, and 561 kilometers that are being converted for natural gas service. The major natural gas pipelines are the 340-kilometer Mariquita to Cali (TransGas Occidente), the 575-kilometer Ballena to Barrancabermeja (Centragas), and the 780-kilometer Barrancabermeja to Neiva to Bogota (Centro Oriente). A map of Colombia's natural gas transmission system is shown in Figure 5.

Plans are in development to build a $250 million natural gas pipeline parallel to the Ballena-Barrancabermeja pipeline to improve the supply to central Colombia, which would transport output from the Chuchupa, Ballena and Rioacha fields (almost 3 TCF in total reserves). A pipeline from Venezuela to central Colombia has also been proposed, but it is unlikely to move ahead given the adequate supplies of natural gas in the area.

In late 1999, Colombian officials announced support for a Colombian-driven regional natural gas grid that would extend into Ecuador and Panama, and then eventually to other Central American countries. The Colombia-to-Panama pipeline is a planned 18-inch diameter line that would be 592 kilometers long and run from the Colombian port of Cartagena to Colon, Panama. This $300 million pipeline would initially transport 70 million cubic feet (MCF) per day, with expansion to 140 MCF per day possible a few years later. The gas would initially come from Texaco's fields in the Guajira region, where it is currently being reinjected to boost crude output, and instead be used to generate power in Enron's Bahia Las Minas thermoelectric power plant in Panama. This pipeline would serve to further spur investment in developing Colombia's natural gas resources.

Railroads

Empresa Colombiana de Vias

Ferreas (Ferrovias), the Colombian National Railroad Company, provides

administration, maintenance, upgrading, and control of the railway system. Of

the 3,154 kilometers that were in existence in 1961, only about 2,000 kilometers

are now in use; the remainder have been lost primarily due to lack of

maintenance of the rails, bridges, and stations. The most important line of the

system is the Bogota to Santa Marta line, which connects the main internal

production and consumption centers with Caribbean Sea ports and allows the

mobilization for the exportation of products such as coffee, oil by-products,

paper, iron, and coal. The most important section of the line runs from La Loma

to Santa Marta and handles the large volume of coal headed for export from the

Drummond Pribbenow Mine in Cesar departamento. The other major railroad line is

the Cerrejon railroad, which carries coal to Puerto Bolivar for export. The

primary users of this line are the CdelC-Intercor association and other mine

operators in the southern part of La Guajira departamento.

Estimates are that only about 10% of the rail system capacity is currently being utilized. To recover the railway system, the Colombian government and Ferrovias have committed to assembling a concession program to attract the private sector into rehabilitating, maintaining, and controlling the operations of the railway system. The Atlantic network was awarded as a concession to Fenosa S.A., which will be responsible for its rehabilitation (at a cost of about $205 million). The Pacific network was awarded as a concession to Concesionaria de la Red del Pacifico. The Colombian government has committed to contribute funds for the first five years of both concessions.

Port Facilities

Colombia's major Caribbean

shipping ports are Coveñas, Barranquilla, Cartagena, and Santa Marta; its major

ports on the Pacific Ocean are Buenaventura and Tumaco. Colombian crude oil is

exported from Coveñas to the Gulf and East Coasts of the United States, while

the port of Tumaco is used to ship crude oil to the U.S. West Coast. In

addition, Drummond Ltd., a U.S.-based coal firm, has a Caribbean port facility

that it uses to export coal from Colombia.

Plans are on the table for the construction of three additional port facilities on the Caribbean coast, at Bahia Concha, Santa Marta, and Cienaga in Magdalena departamento, specifically for coal export. The Colombian government is withholding final approval for these pending resolution of some environmental issues. Another plan being developed by a number of operators and producers in Cesar departamento (being led by Prodeco, a local subsidiary of Glencore) calls for a new $165 million port with a handling capacity of 15 million tons per year. Plans are also underway to enhance coal handling and transportation at Puerto Bolivar, the coal shipping terminal for Cerrejon Zona Norte and other nearby mines. At present, the rail line from the mines to Puerto Bolivar and the port can only handle 24.8 million tons per year. The improvements would improve output from Cerrejon Zona Norte and the Cerrejon Central and Sur mines to more than 44.8 million tons per year.

Electricity

Installed

Capacity

Colombia has historically been greatly dependent on

hydroelectric power for its electricity needs, with about two-thirds of

installed generating capacity now being hydroelectric. Over the past decade,

Colombia's generating capacity has increased by about 50%, reflecting the

burgeoning demand for power in the country.

Severe droughts in recent years have caused power shortages and resulting forced rationing. As a result, Colombia has encouraged development of more non-hydroelectric electricity generation capacity, with a goal of at least 20% shares for both coal-fueled and gas-fueled power generation. Colombia is planning to increase its thermal generation capacity to 50% of its total capacity by 2010.

An historical summary of electricity generation capacity in Colombia is shown in Table 9.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Hydroelectric | 6.67 | 6.61 | 6.71 | 6.79 | 7.70 | 7.90 | 7.88 | 8.06 | 8.14 | 8.20 | 8.57 |

| Nuclear | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Geothermal/Solar/ Wind/Biomass |

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Conventional Thermal | 2.12 | 2.24 | 2.89 | 4.23 | 4.49 | 4.76 | 4.77 | 5.46 | 6.47 | 4.62 | 4.65 |

| Total Capacity | 8.79 | 8.85 | 9.60 | 11.02 | 12.19 | 12.66 | 12.65 | 13.51 | 14.61 | 12.82 | 13.22 |

Generation and Consumption

With the

exception of the drought-ridden year of 1992, electricity demand in Colombia has

grown steadily since 1989. Future demand for electricity in Colombia is expected

to grow about 4.4% per year through 2020. An historical summary of electricity

production and consumption in Colombia is shown in Table 10.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Net Generation hydroelectric nuclear geo/solar/wind/biomass conventional thermal |

35.6 27.2 n/a 0.2 8.1 |

36.3 27.2 n/a 0.2 8.9 |

33.1 22.2 n/a 0.3 10.6 |

37.8 27.7 n/a 0.3 9.8 |

41.0 32.0 n/a 0.3 8.8 |

44.6 33.9 n/a 0.4 10.3 |

42.7 34.3 n/a 0.5 7.9 |

44.3 30.9 n/a 0.5 12.9 |

45.3 31.2 n/a 0.6 13.6 |

43.4 33.2 n/a 0.5 9.7 |

43.3 31.7 n/a 0.4 11.2 |

| Net Consumption | 33.3 | 34.0 | 31.1 | 35.4 | 38.5 | 41.8 | 39.9 | 41.3 | 42.2 | 40.4 | 40.3 |

| Imports | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Exports | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Industry Overview

There are many players

in Colombia's electricity generation market. The largest are EMGESA (in the

Bogotá region), which owns about 2,500 MWe of capacity (though most of it

is hydroelectric), and EPM (in the Medellín region), which owns about

2,600 MWe of capacity (again, mostly hydroelectric). The largest

non-hydroelectric generator in Colombia is Termobarranquilla S.A. (TEBSA) in the

northern Atlántico departamento, which also owns the largest thermal-electric

power plant in Colombia, a 890 MWe gas-fueled facility in Barranquilla that

consists of five combined cycle and two single cycle turbine units. A summary of

Colombia's thermal-electric power plants is shown in Table 11.

| Generating Facility | Owner | Location | Fuel | Capacity (MWe) | |

| City | Departamento | ||||

| Conventional Thermal Power Plants | |||||

| Paipa | Empresa de Energia de Boyacá |

Paipa | Boyacá | Coal | 346 |

| Termoguajira | CORELCA | Riohacha | La Guajira | Natural Gas; Coal |

320 |

| Zipa | EMGESA | Tocancipa | Cundinamarca | Coal | 236 |

| Cartagena | Termocartagena | Cartagena | Bolívar | Natural Gas; Oil |

191 |

| Tasajero | Termotasajero | Cúcuta | Norte de Santander | Coal | 163 |

| Barranca 1 - 3 | Electrificadora de Santander |

Barrancabermeja | Santander | Natural Gas | 91 |

| Yumbo | Central Hidroeléctrica del Rio Anchicayá |

Yumbo | Valle de Cauca | Coal | 31 |

| Diesel Engine Power Plants | |||||

| Planta San Andrés | Electrificadora de San Andrés |

Punta Evans | San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina |

Oil | 55 |

| Cano Limon Field | Occidental Petroleum | n/a | Arauca | Oil | 34 |

| Ibague Factory * | Cementos Diamante de Ibague |

Ibague | Tolima | Oil | 25 |

| Leticia | Inst. Colombiano de Energia Elec. |

Leticia | Amazonas | Oil | 12 |

| Gas Turbine Combined Cycle Power Plants | |||||

| TEBSA | TEBSA | Barranquilla | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 750 |

| Termosierra | EPM | Puerto Parra | Antioquia | Natural Gas | 500 |

| Termocentro | ISAGEN | Cimitarra | Santander | Natural Gas | 290 |

| Termovalle | Termovalle | Yumbo | Valle de Cauca | Natural Gas | 240 |

| TermoEmcali | Emcali; InterGen |

Yumbo | Valle de Cauca | Natural Gas | 235 |

| Las Flores 1 | Central Termoeléctrica las Flores |

Barranquilla | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 156 |

| Conventional Gas Turbine Power Plants | |||||

| TermoCandelaria | TermoCandelaria | Cartagena | Bolívar | Natural Gas | 316 |

| Las Flores 2 & 3 | Central Termoeléctrica las Flores |

Barranquilla | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 252 |

| Mamonal * | AES Bolivar | Cartagena | Bolívar | Natural Gas | 166 |

| Meriléctrica | Meriléctrica | Bucaramanga | Santander | Natural Gas | 160 |

| Barranquilla | TEBSA | Barranquilla | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 140 |

| Proeléctrica | Proeléctrica | Cartagena | Bolívar | Natural Gas | 92 |

| Barranca 4 & 5 | Electrificadora de Santander |

Barrancabermeja | Santander | Natural Gas | 54 |

| Termodorada | Central Hidroeléctrica de Caldas |

La Dorada | Caldas | Natural Gas | 52 |

| La Union | Electranta | n/a | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 49 |

| Chinu | Electrocosta | Chinu | Córdoba | Natural Gas; Oil |

45 |

| Gualanday * | Ecopetrol | Cali | Valle de Cauca | Natural Gas | 41 |

| Termocoa * | Ecopetrol | Apiay Refinery | Meta | Natural Gas | 41 |

| Palenque | Electrificadora de Santander |

Giron | Santander | Natural Gas | 15 |

| Riomar | Electranta | n/a | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 10 |

| Generating Facility | Owner | City | Departamento | Fuel | Capacity (MWe) |

| Location | |||||

Future thermal-electric capacity increases, as expected, favor natural gas as the fuel of choice, though there will also be new power plants that take advantage of Colombia's coal resources. A summary of of Colombia's planned thermal-electric power plants is shown in Table 12.

| Generating Facility | Owner | Location | Fuel | Capacity (MWe) |

Status | |

| City | Departamento | |||||

| Conventional Thermal Power Plants | ||||||

| GenerCauca | GenerCauca | Puerto Tejada | Cauca | Coal | 160 | Planned |

| Petrosur | Petrosur | Guachucal | Nariño | Oil | 150 | Planned |

| TermoCauca FB | Termocauca | Santander de Quilichao |

Cauca | Coal | 100 | Planned |

| Térmica San Bernadino FB | Somos Energía del Cauca |

San Bernardino | Cauca | Coal | 50 | Planned |

| Gas Turbine Combined Cycle Power Plants | ||||||

| TermoBiblis | Electroenergía | Cartagena | Bolívar | Natural Gas | 1,000 | Planned |

| Termo Lumbí | ISAGEN | Mariquita | Tolima | Natural Gas | 300 | Planned |

| Termo Yarigüies | ISAGEN | Barrancabermeja | Santander | Natural Gas | 225 | Planned |

| Las Flores 4 | Central Termoeléctrica las Flores |

Barranquilla | Atlántico | Natural Gas | 150 | Planned |

| Conventional Gas Turbine Power Plants | ||||||

| Termo Upar | ISAGEN | La Paz | Cesar | Natural Gas | 300 | Planned |

| Térmica del Café | Promotora Térmica del Café |

Yopal | Casanare | Natural Gas | 215 | Planned |

Colombia's experience with economic and financial instruments for sustainable development dates back to 1959, when the country's first environmental and development authorities were created. These authorities were primarily compensatory financial instruments. They sought compensation for environmental damage associated with the use of different natural resources, but were not designed to and did not modify the behavior of the deteriorating or polluting agents. Some of these financial instruments included water and forest user charges, air and water effluent charges, transfers from the electric power sector for watershed conservation, and royalty transfers to regional environmental authorities. The common denominator for all of these instruments is that they were not part of an integral strategy to attain specific environmental goals.

Colombia was one of the first Latin American countries to implement legislation requiring environmental impact assessments (EIAs). The first of these programs was established in 1974 under Law 2811. INDERENA, the first Colombian environmental protection agency, was responsible for administering the EIA requirements. The law required developers to prepare impact statements and environmental and ecological studies as a step to obtain environmental licenses. The purpose of licensing was to prepare an environmental plan that showcased activities aimed at mitigating environmental impact.

Between 1991 and 1993, Colombia's Department of Natural Planning appraised the effectiveness of the EIA, and found that the existing regulations gave government officials too much discretion over the manner in which EIAs were conducted. Following the appraisal in 1993, the Colombian Congress phased out INDERENA and created the Ministry of the Environment through Law 99. The Ministry of the Environment is now Colombia’s highest environmental authority. Law 99 established a system of shared responsibility for EIAs. Law 99 requires an environmental license for the execution of projects and the establishment of industries or development activities that may cause natural resource or environmental damage. By 1997 the environmental license became the main regulatory mechanism in Colombia.

A primary cause of environmental damage to habitats in Colombia is by insurgent terrorist attacks on oil and gas pipelines and, to a lesser extent, on electric transmission towers. A 1998 report by the Colombian Ministry of the Environment showed that oil spills, primarily from the heavily bombarded Cano Limon-Covenas pipeline, have caused severe damage to some of the country's rivers and wetlands, wildlife, and farmland. The bombing campaigns over the last ten years have resulted in the spilling into watercourses of more oil than that which was spilled in the Exxon Valdez incident in Alaska.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Because Colombia

possesses abundant fossil fuel resources, the majority of carbon emissions are

from consumption and flaring of these fuels. Over the past decade, Colombia's

carbon dioxide (CO2 )emissions from fossil fuel consumption have

increased by about 40%. Most of Colombia's CO2 emissions are

related to use of petroleum. An historical summary of CO2

emissions from fossil fuel use in Colombia is shown in Table 13.

| Component | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

| CO2 from coal | 1.75 | 3.18 | 3.59 | 3.69 | 3.20 | 2.66 | 2.77 | 3.39 | 3.46 | 2.67 | 2.88 |

| CO2 from natural gas | 2.11 | 2.16 | 2.26 | 2.19 | 2.26 | 2.35 | 2.45 | 3.04 | 3.21 | 2.71 | 2.91 |

| CO2 from petroleum | 7.39 | 7.64 | 8.64 | 9.02 | 9.08 | 9.58 | 10.14 | 10.53 | 10.73 | 10.22 | 10.02 |

| Total CO2 from all fossil fuels |

11.25 | 12.98 | 14.48 | 14.90 | 14.55 | 14.59 | 15.37 | 16.97 | 17.40 | 15.60 | 15.81 |

Colombia has a free market economy with major commercial and investment links to the U.S. Transition from a highly regulated economic regime to an unrestricted access market has been underway since 1990. The Colombian economy was opened to foreign competition in 1991. Foreign investment legislation was revised in 1995 to facilitate joint ventures and other forms of investment. Joint ventures and licensing agreements have become more important recently as businesses strive to be more competitive.

Privatization projects in Colombia must receive congressional approval, which can delay the process. Currently, government officials are holding back on some sales due to political pressure by labor unions and activist groups that are demanding that state-owned assets not be "given away."

The governmental agency primarily responsible for the privatization of state assets is the Council for Economic and Social Policy (CONPES). In June 2002, CONPES sanctioned the sale of the government's majority stakes in 13 regional electric utilities, most of which own generating assets. These were first proposed to be sold back in 1999, but with that looming over them, the companies saw no reason invest any more money to improve their operations. Partly because of this neglect, they have now accumulated a total of about $217 million in debt.

Government efforts to sell-off state assets in the energy sector beginning in the mid nineties have been met with mixed results. The mid- to late-1990s saw the privatization and concession of many Colombian seaports, airports, highways, energy projects, and telecommunications institutions. Colombian natural gas companies were also privatized, with the transmission company Promigas being acquired by a consortium that included Enron and gas distribution infrastructure acquired by Spain's Gas Natural group.

In 1999, Colombia negotiated a $2.7 billion loan package with the IMF to support the government's economic reform program for 2000-2002. As part of the arrangement Colombia promised to divest itself of state-owned companies, including coal producer Carbocol, electricity transmission company ISA, and electricity generator ISAGEN. However, plans to privatize ISA ran into problems in the face of determined opposition, so as an alternative, the government has used public stock offerings to reduce its stake as well as infuse the company with additional capital. In April 2002, ISA commenced a stock offering of 120 million shares (equivalent to 10.74% of the company) to the public. The sale was expected to bring in $55 million and increase minority ownership in the company from 13.3% to 23%. This was the second public offering for ISA; the initial offering, in late 2000, raised $45 million and diluted the national government's ownership from 76% to 66% as well as reducing the stake held by ISA's second largest shareholder, EPM, from 13.7% to 11.9%.

EPM has been trying to acquire the Colombian government's 75.8% interest in ISAGEN, but the deal has been hung up in court over antitrust considerations; EPM is already Colombia's largest capacity electricity generator, while ISAGEN is presently the third-largest capacity generator. The Colombian government, faced with the difficulty of selling off the major state-run companies, has been focusing its privatization efforts on the sale of smaller troubled utilities.

Historically, the Colombian economy has been one of the most stable in all of Latin America. Gross domestic product (GDP) and inflation figures for the past sixty years point to an excellent economic performance within the context of Latin America. Colombia's economic growth has consistently been higher than the Latin American average; its inflation rate has also been historically relatively low compared to other Latin American countries -- in the 1990s, the average inflation rate in Latin America ranged between 200% and 300%, while Colombia's inflation rate remained below 30%. Recognized for its economic stability, Colombia became one of the first two Latin American countries (along with Chile) to receive investment grade ratings for their foreign debt from leading credit rating agencies.

The economic outlook for Colombia is one of limited GDP growth. The country has been recovering from a severe recession in 1998-99 which saw the economy shrink by 4% -- the first yearly drop for Colombia since 1932. The outlook for 2002 was about 1% growth, with about 2.5% growth predicted for 2003. Unemployment is a persistent problem, hitting a record 20% in 2000. An historical summary of some of Colombia economic indicators is shown in Table 14.

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| GDP Growth, percent | 5.7 | 5.3 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.6 | -4.2 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| Consumer Price Inflation, percent | 22.6 | 19.5 | 21.6 | 17.7 | 16.7 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 7.0 |

| Exchange Rate, pesos/US$ | 826 | 926 | 1,036 | 1,143 | 1,536 | 1,874 | 2,229 | 2,291 | 2,865 |

Colombia had once been a closed economy for commercial export that radically protected domestic production. In 1990, under the administration of former President César Gaviria Trujillo (1990-1994), the contemporary economic structure began to take shape. There was a series of economic modifications that brought the country its highest levels of growth and most favorable economic conditions in twenty years. The administration under former President Ernesto Samper Pizano (1994-1998), however, was widely considered to be corrupt and lacking in credibility. Economic growth during his administration slowed and economic imbalances widened.

The administration of former President Andrés Pastrana Arango (1998-2002) took a number of important steps which proved beneficial to the economy. He moved ahead with a serious macroeconomic package that paved the way for recovery, including passage of a tough budget for 2000 and successful flotation of the Colombian peso following a series of controlled devaluations. In mid-September of 2000 the Pastrana administration submitted a tax reform proposal to Congress as part of its structural reform efforts agreed to with the IMF. The tax reform proposal is integral to the government's larger plan to remove structural impediments to improve fiscal balances.

In late 1999, Colombia received approval from the IMF for a three-year $2.7 billion credit under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) to support Colombia's economic reform program for 2000-2002. The Colombian government's agreement with the IMF commits it to maintaining a declining path for inflation and fiscal deficit while increasing growth. Also in late 1999, Colombia received notification from the World Bank that they would receive a $4.2 billion package that complemented the IMF program. The World Bank package included backing from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), the Corporacion Andina de Fomento (CAF), and the Fondo Latinoamericano de Reservas (FLAR).

Colombia is America's 4th largest export market in Latin America after Mexico, Brazil, and Venezuela (which is almost equal with Colombia). Globally, Colombia ranks 25th as a market for U.S. products. Proximity and the established presence of U.S. products and investments in the market contribute to the continued success of U.S. companies in Colombia. Nearly 43% of Colombia exports went to the United States in 2001. Other important export markets include Venezuela (14.2%) and Ecuador (5.5%). Colombia's biggest import partners in 2001 were the United States (34.8%), Venezuela (6.3%), and Mexico (4.7%). Major export products include petroleum and coal (34.5%), chemicals (14.4%), coffee (6.2%), apparel, bananas, and cut flowers. Leading imports are industrial equipment, transportation equipment, consumer goods, chemicals, and paper products. The primary exports (on a cost basis) from the United States to Colombia are machinery and transportation equipment, and chemicals and related products. The primary export from Colombia to the United States is crude oil. An historical summary of Colombia's trade balance is shown in Table 14.

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| Imports (billion US$) | 14.6 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 12.6 |

| Exports (billion US$) | 10.9 | 11.6 | 13.2 | 12.3 | 11.8 |

Excellent opportunities for exports to Colombia exist in oil and gas exploration equipment and services. Another promising prospect is electrical power systems, provided that the regaining economic strength of Colombia continues, as does its rising demand for energy. Colombia's Ministry of the Environment estimates that the country’s environmental investment needs will total around $34 billion during the next decade. The best opportunities include water and wastewater treatment plants, water and air monitoring and control equipment, solid waste hauling and disposal equipment, and environmental services. Expected future expansion within the coal mining industry in Colombia will provide opportunities for additional mining equipment exports, including shovels, excavators, front loaders and related equipment.

During the first half of the 1990s, Colombia began lowering and simplifying its import tariffs in order to reform its foreign trade regime and open up the economy to foreign investment. Colombian imports are classified into three basic groups: those freely imported, those requiring approval of a previous import license, and items that cannot be imported. All imports must be registered with the Colombian Foreign Trade Institute (INCOMEX) in a special application form known as 'Registro de Importacion'. There are four common external tariff levels in Colombia based on whether the import is not produced in Colombia (5% tariff), is produced in Colombia (10-15%), is a finished good (20%), and some exceptions, such as automobiles which remain at the level of 35-40%, and some agricultural products which fall under a variable import duty system. The countries comprising the Andean Community have agreed upon this tariff system for imports from third party countries.

Since 1991, the Colombian government has implemented policies that do not discriminate against foreign investors and has aimed to treat domestic and foreign investors equally. Investment restrictions in various sectors have been eliminated, with the exception of those activities that relate to national security and toxic waste. As a result, the country has seen a significant increase in foreign investment since 1991. An historical summary of foreign investment in Colombia is shown in Table 15.

| Year | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 |

| Total Investment (billion US$) |

311 | 797 | 894 | 1,809 | 2,170 | 2,963 | 4,541 | 4,750 | 4,382 |

Some of the advantages that Colombia has to offer to foreign investors include duty-free zones, which were established to promote export of industrial products; special foreign trade rules; special tax rules, such as the Tax Refund Certificate (CERT), which was created so that exporters could use it to pay income taxes, tariffs and other taxes; the Paez Law and Quimbee Decrees which promote investment in regions affected by natural disasters; and finally, special trade zones comprised of free trade zones and special economic export zones (SEEZ).

Free trade zones were created in 1958 when the Colombian government established the Barranquilla Free Industrial and Trading Zone. Free trade zones are geographic areas that have certain tax benefits, special regulations for capital investment, foreign exchange benefits, and procedural incentives; the types of free trade zones are industrial, commercial, tourist, and technological. By Law 7 and Decree 2131 in 1991, the Colombian government authorized the liquidation of the public free trade zone assets and personnel by July 1994. Five government-owned zones were given for administration to the private sector through a concession contract. Authorized by Law 7, the private sector has also constructed six more free trade zones.

SEEZs are geographical areas provided with special conditions that promote the combination of private capital and potential foreign investment. Colombia has four SEEZs for exporting purposes; operators in a Zone must export a minimum of 80% of their production. Incentives to attract investors include customs tax and value-added tax exemptions on imports for companies that set up operations in a zone. Colombia is seeking to increase its export volume by creating favorable conditions in these zones to attract investors.

Numerous foreign companies maintain activity in Colombia. Companies such as Exxon-Mobil, Chevron, Texaco, BP Amoco, Arco, Conoco, Triton, Harken, Shell, Elf Aquitaine, Total, Repsol, Lasmo, PetroCanada, Canadian Petroleum, Petrobras, Teikoku, Nexen, Inc. (formerly Occidental), Enron and others continue to play a role in Colombia's oil and gas industries. U.S.-based Drummond Ltd. plays a major role in Colombia's coal mining operations. General Electric, AES, and the Chilean-based firms of ENDESA and Gener S.A. are involved in Colombia's electric industry.

| For more information, please contact our Country Overview Project Manager: |

Richard

Lynch U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy 1000 Independence Avenue Washington, D.C. 20585 USA telephone: 1-202-586-7316 |

|

Return to Colombia

page |

| last updated

on February 6, 2003 | Comments On Our Web Site Are Appreciated! |