Climate Deal Announced, but Falls Short of ExpectationsDec 18, 2009 - Helene Cooper and John M. Broder - The New York Times

COPENHAGEN -- Leaders here concluded a climate

change deal on Friday that the Obama administration

called “meaningful” but that falls short

of even the modest expectations for the summit meeting

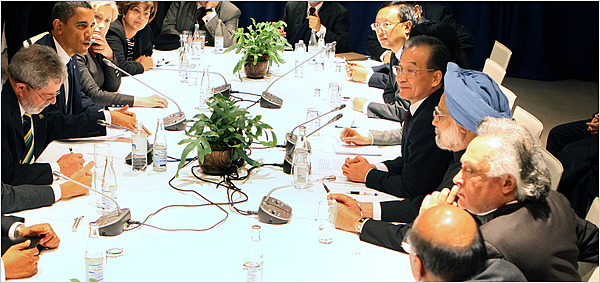

here. Even an Obama administration official conceded, "It is not sufficient to combat the threat of climate change, but it’s an important first step." "No country is entirely satisfied with each element,” the administration statement said, “but this is a meaningful and historic step forward and a foundation from which to make further progress." The accord drops the expected goal of concluding a binding international treaty by the end of 2010, which leaves the implementation of its provisions uncertain. It is likely to undergo many months, perhaps years, of additional negotiation before it emerges in any internationally enforceable form. "We entered this negotiation at a time when there were significant differences between countries," the American official said. "Developed and developing countries have now agreed to listing their national actions and commitments, a finance mechanism, to set a mitigation target of two degrees Celsius and to provide information on the implementation of their actions through national communications, with provisions for international consultations and analysis under clearly defined guidelines." The deal came after a dramatic moment in which Mr. Obama burst into a meeting of the Chinese, Indian and Brazilian leaders, according to senior administration officials. Chinese protocol officers protested, and Mr. Obama said he did not want them negotiating in secret. The intrusion led to new talks that cemented key terms of the deal, American officials said. Sergio Serra, Brazil, senior climate negotiator here, confirmed that Mr. Obama had 'joined' a meeting of Brazilian, Indian, Chinese and other officials, although he did not say that Mr. Obama walked in uninvited. "After several discussions had taken place they were joined by President Barack Obama,” Mr. Serra said. “Several important decisions were taken — not a few due to Brazilian mediation — that we hope will bring a result, if not what we expected, that may be a way of salvaging something and pave the way to another meeting or series of meetings to get the full result of this proceeding." The agreement is believed to follow the form of a draft accord that was circulating here early Friday evening. In that draft, developed nations committed to a long-term target of reducing their greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent by 2050. No specific mid-term target was set. The draft dropped earlier language that said a binding accord should be reached "as soon as possible," and no later than at the next meeting of the parties, in Mexico City in November 2010. Instead, the draft set no specific deadline, saying only that the agreement should be reviewed and put in place by 2016. The draft also included a few hard figures about joint emissions cuts of 50 percent by 2050. It included a dozen or so enumerated points asserting general commitment to the idea that “climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time” and asserted that “deep cuts” in global emissions are required. It also sought to lay out some framework for verification of emissions commitments by developing countries and establish a "high-level panel" to assess financial contributions by rich nations to help poor countries adapt to climate change and limit their emissions. Friday morning, President Obama, speaking to world leaders gathered here at the frenzied end of two weeks of climate talks, urged them to come to an agreement -- no matter how imperfect -- to address global warming and monitor whether countries are in compliance with promised emissions cuts. His remarks appeared to be a pointed reference to China's resistance on the issue of monitoring, which has proved a stubborn obstacle at the talks and a source of tension between China and the United States, the two largest emitters of greenhouse gases. After delivering the speech to a plenary session of 119 world leaders, Mr. Obama met privately with China's prime minister, Wen Jiabao, in an hourlong session that a White House official described as 'constructive.' However, in a day of high brinkmanship and seesawing expectations, Mr. Wen did not attend two smaller, impromptu meetings that Mr. Obama and United States officials conducted with the leaders of other world powers, an apparent snub that infuriated administration officials and their European counterparts and added more uncertainty to the proceedings. At 7 p.m. Copenhagen time, Mr. Obama and Mr. Wen met again, joined by Prime Minister Mammoghan Singh of India and President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil. Earlier in the day, in his address to the plenary session shortly after noon, Mr. Obama, clearly frustrated by the absence of an agreement, was both emphatic and at times impatient. "The time for talk is over," he said.

But, he added, "I'm confident we’re moving in the direction of final accord." The announcement came on a day filled with high brinksmanship and seesawing expectations. On Friday morning, President Obama, speaking to world leaders gathered here at the frenzied end of the two weeks of climate talks, urged them to come to an agreement — no matter how imperfect — to address global warming and monitor whether countries are in compliance with promised emissions cuts. His remarks appeared to be a pointed reference to China’s resistance on the issue of monitoring, which has proved a stubborn obstacle at the talks and a source of tension between China and the United States, the two largest emitters of greenhouse gases. After delivering the speech to a plenary session of 119 world leaders, Mr. Obama met privately with China's prime minister, Wen Jiabao, in an hourlong session that a White House official described as "constructive." But Mr. Wen did not attend two smaller, impromptu meetings that Mr. Obama and United States officials conducted with the leaders of other world powers, an apparent snub that infuriated administration officials and their European counterparts and added more uncertainty to the proceedings. Earlier in the day, in his address to the plenary session shortly after noon, Mr. Obama, clearly frustrated by the absence of an agreement, was both emphatic and at times impatient. "The time for talk is over," he said. He arrived here prepared to lend his political muscle to secure an agreement on climate change at negotiations that have been plagued by distrust over a range of issues, including how nations would hold each other accountable. "I don't know how you have an international agreement where you don't share information and ensure we are meeting our commitments," he said. "That doesn't make sense. That would be a hollow victory." Within an hour of Air Force One’s touchdown in Copenhagen on Friday morning, Mr. Obama went into an unscheduled meeting with a high-level group of leaders representing some 20 countries and organizations. Mr. Wen did not attend that meeting, instead sending the vice foreign minister, He Yafei. Mr. Wen did, however, meet privately with Mr. Obama for 55 minutes shortly after the American president’s eight-minute speech to the plenary session. The two leaders "took a step forward and made progress," a White House official said, after the meeting that broke up a little after 1:35 p.m. Copenhagen time. The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the continuing negotiations, said that the two men touched on all of the three issues Mr. Obama raised during his speech: emissions goals from all critical countries, verification mechanisms and financing. Mr. Obama and Mr. Wen asked their negotiators to meet with one another and with other countries "to see if an agreement can be reached," the White House official said. Still, it was unclear how much progress had occurred. After a lunch break, President Obama returned to another session with leaders of the same countries that he had met with Friday morning -- Australia, Britain, France, Germany, Japan, India, South Africa, Brazil -- and Mr. Wen once again sent another emissary in his place, a special representative, Yu Qingtai, White House officials said. On a separate issue, later in the day, Mr. Obama was to meet with President Dmitri A. Medvedev of Russia, as the two were to negotiate to replace an expired nuclear arms control treaty. In speaking to the plenary session, Mr. Obama stressed the urgency of reaching a climate accord, no matter how "imperfect" it might have to be. "We are running short on time," he warned. "And at this point, the question is whether we will move forward together, or split apart. Whether we prefer posturing to action. "We can again choose delay, falling back into the same divisions that have stood in the way of action for years," he said. But he added that this course would leave leaders "back having the same stale arguments month after month, year after year, perhaps decade after decade -- all while the danger of climate change grows until it is irreversible." The United States, Mr. Obama said, is "ready to get this done today." Before Mr. Obama';s speech, President Nicolas

Sarkozy of France said that China was holding

back progress in the climate talks and that Chinese

resistance to monitoring of emissions was a crucial

sticking point. He stressed that China was trying to reduce the rate of growth of its emissions voluntarily "in light of its national circumstances." He added: "We have not attached any condition to the target or linked it to the target of any other country. We are fully committed to meeting or even exceeding the target." Negotiators here had worked through the night, charged with delivering a draft of the political agreement by 8 a.m. ahead of the arrival of dozens of heads of state and high-level ministers for the final stretch of deliberations. An American negotiator, weary from a night of discussions, expressed confidence early Friday that the talks would produce some form of an agreed declaration, even if it lacked specifics on some of the toughest issues. Mr. Obama injected himself into a multilayered negotiation that has been far more chaotic and contentious than anticipated -- frozen by longstanding divisions between rich and poor nations and a legacy of mistrust of the United States, which has long refused to accept any binding limits on its greenhouse gas emissions. The administration provided the talks with a palpable boost on Thursday when Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton declared that the United States would contribute its share to $100 billion a year in long-term financing to help poor nations adapt to climate change. Mrs. Clinton's offer came with two significant conditions. First, the 192 nations involved in the talks here must reach a comprehensive political agreement that takes effect immediately. Second, and more critically, all nations must agree to some form of verification -- she repeatedly used the term "transparency" -- to ensure they are meeting their environmental promises. China has brought the talks to a virtual standstill all week over this issue, which its leaders claim to be an affront to national sovereignty. But the Chinese resistance on the issue is matched in large measure by Mr. Obama's own constraints. The Senate has not yet acted on a climate bill that the president needs to make good on his promises of emissions reductions and on the financial support that he has now promised the rest of the world. |

Email this page to a friend

If you speak another language fluently and you liked this page, make

a contribution by translating

it! For additional translations check out FreeTranslation.com

(Voor vertaling van Engels tot Nederlands)

(For oversettelse fra Engelsk til Norsk)

(Для дополнительных

переводов проверяют

FreeTranslation.com )