8 July 1995 No 1985

Weekly £1.70

New Scientist:

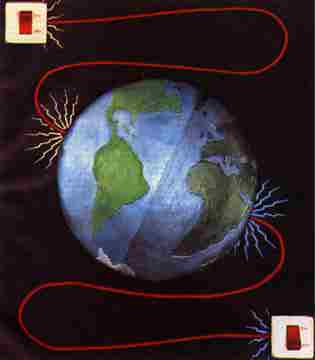

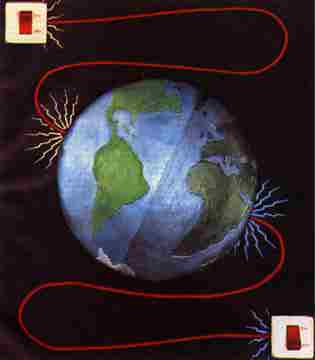

GLOBAL POWER — The electric hypergrid

THE INTERNATIONAL GRID

WHEN

Arab energy ministers met in Cairo in April, there

was one thing at the top of their agenda-plans

for a regional electricity grid that would stretch

more than 5000 kilometres from Morocco in the

west to the Gulf states in the east. And for Maher

Abaza, Egypt's energy minister and the meeting's

host, that would only be the start. Abaza foresees

a network, with Egypt at its heart, that would

give the energy-hungry countries of Europe access

to the hydropower of Africa's mightiest rivers.

Ultimately, he envisages a worldwide power system

that would cut the cost of electricity everywhere.

This, says Abaza, represents "the hope for the

peoples of the developing world".

Abaza is following in the footsteps

of Richard Buckminster Fuller, the maverick

American architect and futurologist who was

born 100 years ago next week. Buckminster Fuller

is remembered chiefly for his geodesic domes,

but he also dreamt of continents linked by high-voltage

pylons and undersea cables. In the mid-1970s

he predicted that the world would one day have

a global electricity grid. Now engineers are

planning the links that could eventually grow

into an international network, distributing

power from the rainforests of Borneo and the

geothermal rocks of Iceland, the Zaire river

and France's nuclear power plants.

|

Dreams of a global electricity grid are

close to reality. Fred Pearce looks ahead

to a world in which electrical power is traded

worldwide

|

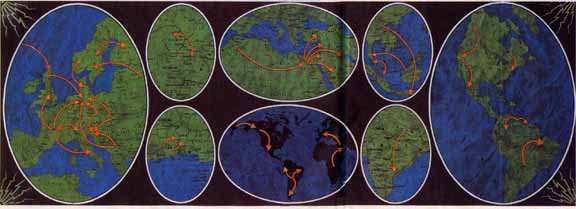

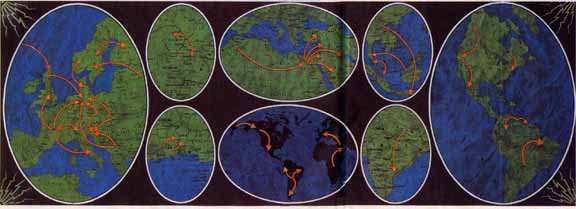

In Anchorage, Alaska, the talk is of a project

to bring hydroelectricity from Siberia to North

America through a submarine power line. The

Bering Strait, which separates Russia and Alaska

is only 85 kilometres wide and 50 metres deep,

but the cable could cost some $2 billion to

lay. "We've put eight years' work into engineering,

geological and environmental studies," says

George Koumal, chairman of the Interhemispheric

Bering Strait Tunnel Group, which wants to combine

the power link with a railway tunnel. Now he

is looking for finance and, in September, comes

to London for a fund-raising conference.

Last November, plans were revived to harness

up to 37 000 megawatts of generating capacity

on the Mekong river, which runs for more than

4000 kilometres from China, through Burma, Laos,

Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Power lines

already straddle the river, linking the site

of the Nam Ngum dam, near Vientiane, to the

Thai border, and construction began this year

on another, much larger "export dam" in Laos

on the Nam Theun river, a tributary of the Mekong.

"It is our hope to build a power grid in the

region that will allow the six countries to

utilise power most efficiently," says Noritada

Morita, director of the Asian Development Bank,

which is contributing funds.

The Mekong links may lead to a larger southeast

Asian grid. Malaysia and Thailand, two of the

world's fastest-growing economies, are planning

cross-border power connections. And, next year,

Malaysia is due to begin building a giant hydroelectric

plant at Bakun on the Balui river in the rainforest

of Sarawak on the island of Borneo. The power

station, capable of generating 2400 megawatts,

will supply electricity to the mainland through

a 650-kilometre cable on the bottom of the South

China Sea. Any power that Malaysia does not

need will go to Brunei or the Indonesian state

of Kalimantan, which between them occupy the

rest of Borneo, or to Singapore, says the Malaysian

government.

|

The Himalayan kingdom of Nepal is another remote

region with a large hydroelectric potential. It currently

has the lowest per-capita energy consumption of any

nation on Earth the capacity of the national system

is just 278 megawatts but, according to its Water

and Energy Commission, could generate more than 40

000 megawatts of hydroelectricity in its steep valleys.

The Arun III hydroelectric project, the first of three

dams on the Arun river, which will generate 1500 megawatts,

is about to receive funding from the World Bank. This

is likely to be followed by another, generating 11

000 megawatts and costing $6 billion, in the Chisapani

Gorge just 45 kilometres from the Indian border. And

Nepal has plans for more than ten other schemes.

Himalayan potential

Nepal is about to build the long distance

power lines to transport the electricity these schemes

will generate. Its first customers will be the great

industrial cities of northern India, a region of 300

million people where rapid industrial development

has led to frequent power cuts. Indian planners are

also eyeing Nepal s Himalayan neighbour, Bhutan, which

has an estimated potential for generating 20000 megawatts

of hydroelectric power.

But at present, the world's largest

exporter of electricity is Paraguay. The Itaipu dam

on the River Parana is the world's biggest power complex

with a capacity of 12 600 megawatts from where power

is fed to Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo in Brazil.

Such vast projects appall many environmentalists,

who point to the ecological damage they can cause.

But not all US Vice-President Al Gore, who is noted

for his environmental concerns, says: "A global energy

network makes enormous sense it we are to meet global

energy needs with a minimal impact on the world's

environment."

Intercontinental electricity grids are the only way

to harness the planets great sources of renewable energy

and link them to centres of population according to

Peter Meisen of Global Energy Network Institute in San

Diego this nonprofit-making organisation is dedicated

to promoting Buckminster Fuller's vision of a global

grid. "Modern transmission lines can efficiently span

up to 6000 kilometres, says Meisen. This is enough to

bring power to large industrial centres from hydroelectric

sites on the great Arctic rivers, such as the Ob and

Yukon, Mackenzie and Lena and tidal power sites in Argentina,

China, Australia and India. A global grid could also

tap solar power right round the tropics and the geothermal

potential of the "ring of fire" round the Pacific Ocean,

in Iceland and in the Rift Valley of Africa.

Modern society is founded on electricity,

in 1990, the world's power stations pumped out enough

power for every person on the planet to run four 60-watt

bulbs permanently. And production is growing fast.

Output was up 134 per cent from 1970 to 1990, while

the global population rose by just 40 per cent. That

puts electricity well ahead of cars (up 124 per cent

in the same time), cigarettes (75 per cent) or oil

(41 per cent).

'Modern

society is founded on electricity. More investment

now goes into distributing than generating it,

and lines of pylons are extending round the globe

faster than roads, connecting two-thirds of the

population' |

More investment now goes into distributing

electricity than generating it, and lines of pylons

are extending round the world faster than roads. Four

billion people, or around two-thirds of the world's

population, are connected to distribution networks,

Many began as local enterprises, but more and more

have become international, so that today more than

50 nations have electrical interconnections with their

neighbours.

Such links can be complex. All grids

run on alternating current, but the frequencies and

other specifications often differ from country to

country, so giant transformers have to be installed

at borders, These usually convert AC power from one

country into direct current and then back into AC

to meet its neighbour's specification. This is expensive.

A link from Germany to the Czech Republic, completed

in 1993, cost $180 million.

International links allow countries

to share their generating capacity, and smooth out

surges in demand. These can occur at various times

of day: during the morning switch-on of factories,

or the evening rush for the kettle at the end of a

popular TV programme, for example. A link can reduce

the number of power stations both partners need to

build to cope with these peaks. Take the submarine

cable linking Britain and France, which came into

service in 1986. In England and Wales, average winter

demand is 38 000 megawatts, but at peak times the

load rises to 47 500 megawatts. France can help out

because it has spare generating capacity and its peak

load comes at different times from Britain's.

Mix and match

Different types of power station have different capabilities,

and international links can help here too. Nuclear power

stations can take several days to switch on or off,

so they are best at providing continuous, "base-load"

electricity, A hydropower generator can be started in

seconds, making it ideal for meeting surges. Switzerland

imports base-load electricity from French nuclear power

plants, but exports power from its Alpine dams in short

bursts to meet France's peak-load needs.

Long-distance power lines may also

allow several countries to benefit from a remote source

of cheap power. The world's ten largest power stations

are all hydroelectric plants, and most of them are

far from their markets. Four are in Siberia three

in remote regions of South America and two in northern

Canada.

The Achilles heel of pylon links is

their vulnerability in wartime. The classic example

is Mozambique's hydroelectric dam on the River Zambezi

at Cabora Bassa, which was completed in 1976. Built

to fuel the gold mines of South Africa 1300 kilometres

away, it is capable of delivering 4000 megawatts of

electricity more than ten times Mozambique's domestic

demand. During two decades of civil war in Mozambique,

the pylon link was regularly cut by antigovernment

guerrillas. Only now, two decades on, can the dam

do the job it was designed for.

But power links can be a force for

Peace. Following the Israel-Jordan peace pact last

October, the two states plan to join their grids.

A World Bank study last year spelt out the advantages.

"As Israel and Jordan have sharply different daily

and weekly load peaking patterns, interconnection

of their national grids would permit mutually profitable

trading between power utilities, and reduce the need

for costly back-up capacity for each country, the

report concluded.

The Bank also proposed connecting

Israel to the Jordan-Egypt link now being built under

the Red Sea, and a large hydroelectric project for

the rift valley between the Red Sea and Dead Sea,

the lowest-lying lake in the world. The scheme would

exploit the 400-metre level difference between the

two seas by building a canal between them and a hydroelectric

power plant on the shores of the Dead Sea. The power

station would spur industrial development in the region,

and power a desalination works that would supply water

to farms and resorts.

During the l950s, the colonial powers

in Africa created several international dams. Besides

Mozambique's Cabora Bassa dam, built by the Portuguese,

the Kariba dam on the Zambezi has, since its construction

in the 1950s, been the mainstay of the interconnected

Zambian and Zimbabwean electricity grids. And Ghana's

Akosombo dam, conceived by the British and executed

shortly after independence, exports power to neighbouring

Togo and Benin.

But some more recent schemes have

collapsed because of lack of funds. The Manantali

dam on the upper reaches of the Senegal river in the

West African state of Mali was completed in 1987.

It was intended partly to generate power for Dakar,

the capital of Senegal more than 1000 kilometres away

on the Atlantic coast. Rut the money ran out and,

almost a decade on, the gaps left in the dam for the

turbines remain empty and the pylon route to Dakar

is no more than a line on the map.

The densest network of links is in

Europe. The countries of mainland Western Europe own

14 per cent of the world's electricity generating

capacity and, for around 50 years, they have been

joined by a system of AC links known as the Union

for the Cooperation of Production and Transmission

of Electricity. The system is connected by DC links

to a Scandinavian grid via Denmark, and to Britain

by the Channel link.

Czech mate

There is a similar network in Eastern Europe, and a

growing number of links between the two. They were being

built even before the Berlin Wall fell In thc 1980s,

Czechoslovak dams began supplying power to Germany and

Austria which also established pylon links with Hungary

and the former Yugoslavia. In mid-1993, the capacity

of the direct connections between West and East Europe

was doubled with the completion by the German and Czech

governments of a DC link near Weiden in Bavaria.

The East European and Scandinavian

grids are both connected to the United Power System,

which cove s the former Soviet Union and taps Siberia

S giant hydroelectric plants. Until 1989 the UPS was

a major exporter of power to Eastern Europe. Since

then industrial decline has reduced the trade.

But within Europe, international trade

in electrical power is rising fast. During the 198Os,

when the amount of power generated increased by half,

the trade in electricity doubled, Austria, France

and Switzerland export more than 10 per cent of their

production, while Finland, Italy and Portugal import

more than 10 per cent of their requirements. Germany

exports power during off-peak hours, but is 1an importer

during peak periods, especially in summer.

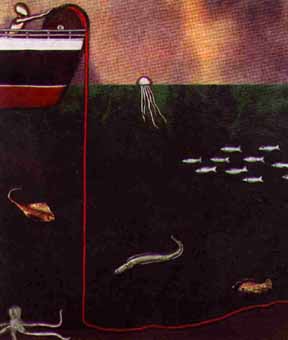

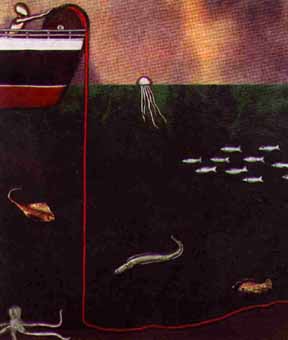

Sea links

The sea is only a minor obstacle to European grid-builders.

The cross-Channel link is 50-kilometres long, and Norway

and Denmark are joined by a 125-kilometre submarine

cable across the Skagerrak. The world's longest submarine

link stretches for 200 kilometres along the bottom of

the Gulf of Bothnia, linking Finland and Sweden. Two

years ago, Icelandic engineers proposed laying a 1000-kilometre

cable beneath the North Atlantic to Scotland, to allow

the island to exploit its hydroelectric and geothermal

potential by selling electricity to Britain and continental

Europe.

In North America, there are two prime grids, both cross-border,

covering the east and west of the US and Canada. Power

from Quebec's hydroelectric plants around James Bay,

with a combined capacity of 15 000 megawatts, is brought

south on five high energy power lines into the northeastern

US. The link provides a tenth of New York City's power.

Opposition from Cree Indians, whose land was to be flooded,

recently halted Hydro-Quebec's plans to double the capacity

of the James Bay complex. "We regard this as a temporary

setback," the giant state enterprise says.

Such regional networks could be the

potential building blocks of a global grid. Besides

the Alaska link, Russian engineers want to export

power from their Siberian dams to the industrial centres

of China, Japan and Korea, the top priority being

a Russia-China link. The two countries plan a cascade

of clams on the Amur river in Manchuria, where it

forms the border between them, before cutting across

Russian territory and into the Pacific Ocean.

While the superpowers shape up for

electrical union, the developing world is looking

to transnational electricity grids to promote economic

development. In 1993, the African Development Bank

agreed to pay for a feasibility study into erecting

a 4000-kilometre power line from Zaire to Egypt, passing

through the Central African Republic, Chad and Sudan.

The idea is to turn the Zaire, the second largest

river in the world, into a power source for much of

northern Africa.

Black power

The river could provide up to 20 000 megawatts of electricity

from one site, the Inga Falls, between Kinshasa and

the Atlantic Ocean. There is already a hydro power station

at the falls which sends electricity south to copper

mines in southern Zaire and Zambia. Twenty years ago,

South Africa proposed expanding its capacity to create

more power for southern Africa, where power lines already

link South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho,

Swaziland and Mozambique. Northern Africa need not worry,

though. The Inga Falls could, in theory, supply more

than twice the current electricity demand of the whole

continent.

The idea of a single site powering

the whole of Africa may be absurd, But as electricity

demand across the planet grows, the case for ever

larger regional electricity grids becomes stronger.

"In future," says Meisen, "it will be possible to

meet Buckminster Fuller's vision of interconnecting

continents A global electricity grid is too large

a project to be built as a single endeavour. But,

like the emerging worldwide grid of transcontinental

highways it could happen nonetheless.

|