Let it shine, let it shine

August 14, 2006 - Jon Ortiz - Sacramento Bee

|

| Beneath the solar panels, the

freezer section at Tony's Fine Foods is one cold

place to work. Solar power runs the 140,000-square-foot

distribution center, with power to spare.

-Sacramento Bee/Bryan Patrick |

How's this for irony? A massive West Sacramento cold-storage

warehouse is being powered by one of California's

biggest privately owned solar energy systems. Summer's

long, hot days are a plus for Tony's Fine Foods, where

5,782 photovoltaic panels mounted on the roof and

grounds generate more than enough energy to run the

company's 140,000 square-foot chilly distribution

center on Reed Avenue.

The $7 million system, which cost about $3.5 million

after Pacific Gas and Electric rebates, is roughly

the size of three football fields and generates enough

electricity to power 850 homes.

"We figure it will save us an average of $22,000

per month on our utility bill," said Scot Berger,

the company's owner and chief financial officer. "But

beyond the savings, it's something that we're proud

to own."

Tony's, which delivers meat, baked goods and other

perishables to grocery stores and restaurants all

over the West Coast, is on the leading edge of a small

but growing number of companies plugging into solar

power as a way to hedge their bets against fluctuating

utility costs.

|

| Scot Berger of Tony's Fine Foods

in West Sacramento checks out the massive photovoltaic

system on the warehouse roof. The system is roughly

the size of three football fields and generates

enough electricity to power 850 homes. -Sacramento

Bee/Bryan Patrick |

To achieve that, Tony's roof and part of a nearby

field are filled with black 3-foot by 5-foot panels

that look like gigantic blank dominoes, angled to

maximize their exposure to the sun.

The setup doesn't have storage batteries, so when

the sun isn't out, the facility draws power from the

local grid.

Solar energy makes up a tiny segment of California's

energy portfolio, accounting for about one-quarter

of 1 percent of the state's total electric consumption.

Still, it is one of the state's fastest growing power

generation segments. The Sacramento Municipal Utility

District figures that the industry statewide will

grow 30 percent to 40 percent each year for the foreseeable

future.

"We've received quite a bit of interest in our service

area," said John Bertelino, head of SMUD's renewable

generation division. "We're working on something with

the Los Rios (Community College) district. Government

agencies, private businesses are interested, too,

everyone from the state Department of General Services

to Ace Hardware and mom-and-pop gas stations."

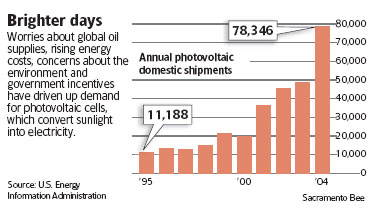

Rising fuel prices, global warming worries and changes

in world events that have spooked oil markets are

prodding companies to think about solar, Bertelino

said.

Mix in federal tax credits and subsidies that bring

down the cost of installing solar systems by 50 percent

or more, and what was once considered a costly fringe

technology starts to look like a sound business move.

Some companies tapping into solar power include:

• Microsoft Corp., which in April activated a 480-kilowatt

system at its Mountain View campus.

• Fetzer Vineyards, which started construction last

month on a 901-kilowatt array to be finished by October

at its Hopland bottling plant.

• Wholesale distributor Coastal Pacific Foods, which

powered up a 723-kilowatt system at its Ontario center.

Tony's executives started looking into solar power

two years ago and contracted Solar Development Inc.

of Roseville last summer to design and install a system.

Japan-based Sharp Electronics Corp. made the cells

in Japan and assembled them into panels at its Memphis,

Tenn., plant. The finished product was then shipped

in nine tractor trailers to West Sacramento.

Solar Development's subcontractors took seven months

to install the solar array, converters and wiring.

The system uses aluminum and stainless steel fasteners

and has no moving parts, so it needs little maintenance

other than occasionally hosing down the panels to

keep them operating at peak efficiency.

Experts say well-made photovoltaic systems last 25

years or more before their capacity to convert sunlight

starts to appreciably degrade.

Tony's flipped the switch in May, activating the

largest solar plant in a commercial business in California,

"and quite possibly the nation," said Kevin Davies,

Solar Development's project manager. "It's certainly

among the biggest, that's certain."

The electricity generated powers Tony's offices,

charges the batteries for 40 pallet movers and 20

electric forklifts, chills its warehouse to 34 degrees

and frosts its 38,000-square-foot frozen food section

to 10 degrees below zero.

Even with all of that, the system still produces

more electricity than Tony's uses. On sunny days the

company's meter runs backwards as the excess automatically

flows into the grid.

"We figure that our cost savings will pay for the

system within seven years," Berger said. "When we

added everything up, it was a no-brainer."

|